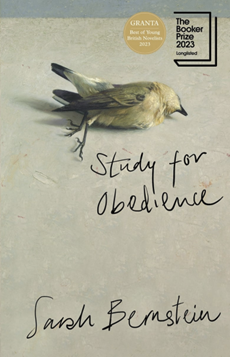

An unsettling portrait of inherited guilt and culpability, told through the lens of an unreliable narrator.

Published by Knopf Canada

208 Pages. Full Length Novel

“I can turn the tables and do as I want. I can make women stronger. I can make them obedient and murderous at the same time.” – Paula Rego

Bernstein gleaned inspiration from feminist painter Paula Rego (1935-2022) while perusing a gallery showcasing, where she found that Rego’s work primarily dealt with themes of obedience, a disposition that is often characterized as feminine and passive in nature. Indeed, in an opening epithet introducing her novel as a finalist, and eventual winner of the 2023 Soctiabank Giller Awards, Bernstein noted that her novel, in turn, is a look at the ‘how systems of domination are disabling to people exerting power, as well as the people subject to it.’

Study for Obedience (2023) is told entirely from first person narration. A woman – who remains unnamed for the duration of the novel – moves to some remote village in a ‘Northern Country’ to take on the role of housekeeper for her older brother (in which she boasted an almost, Freudian-like dynamic with), a businessman whose wife has recently left him. As soon as she moves in, strange occurrences begin to coincide with her appearance, almost disrupting a sense of equilibrium that this village is normally, assuredly, attuned too. A dog is revealed to have been carrying a phantom pregnancy; a potato blight; an inexplicable though sudden arousing of excitement on the part of a herd of cattle; the death of a ewe and her still-born baby. There is a hesitancy, a reluctance on the part of the local townsfolk to welcome her into the quaint community with open arms. Even noting the reception of the townsfolk as reluctant is placing matters lightly; a more accurate description would be an immediate growing hostility to her emergence. Even then, the narrator senses an underlying dread, a mounting threat looming just above the horizon. And who is to blame her? Alone, at least for much of the novel, in this strange town, this foreign country of ‘her forebears’, the novel immediately has such a distinct sense of paranoia and overwhelming dread set against a pastoral yet bleak landscape. Still, much of this novel is opaque, and it is not entirely clear what is going on given the limited narration and predominant internal dialogue. Readers are constantly having to ask if the experiences being relayed are indeed, objective reality or some altered or misconstrued form thereof.

Publishers tend to conflate the chatter around authors, so often in an attempt to encourage hype around a project and its marketability (more on this, shortly). Knopf Canada (Bernstein’s publisher) and Granta have both, with the latter bestowing recognition in the form of their ‘Best Young British Novelists’ of 2023 award, acknowledged Bernstein as ‘one of the most exciting voices of her generation’. This claim is thankfully one that I can at least acknowledge, on some level, as completely accurate. Study for Obedience is so singular, so inventive, so unique, that I am not surprised it has picked up steam in various prestigious awards circuits.

Immediately, it is clear that Bernstein is unconcerned with writing to ascertain a specific readership, or for appeal. Study for Obedience is a prime example of language as art, which can be presumptuous given that literary fiction is often seen as pretentious by default considering the resistance to formula and expectation. I bring up this distinction because reading this novel ostensibly feels both slightly dread inducing, yet completely awe-inspiring in terms of the sheer technical skill on display. Study for Obedience is Bernstein’s second full-length novel, and with her background in poetry in particular and the ability to use language to convey a story where – for all intents and purposes – not much actually happens beyond the blabbering of the unnamed narrator and her internal dialogue, her talent is clear.

This is the kind of story that is more so concerned with tone and technique over subject matter. With allegory and metaphor. A multi-layered story that does not immediately expose itself, even upon completion. The kind of story that could be studied in some advanced English seminar. And, undeniably, the kind of literary fiction title that will not boast major mass appeal. But for readers with an appreciation for literary writing, or writing that elevates language as an art form, this is the prime novel.

I wanted to be good in this terrible world. I thought of the birds. I accumulated fidelities in this space of diminishing returns. On the one hand, I felt that my obedience had been rewarded at last. On the other, in this cold and beautiful countryside, I feared I was living a life in which I had done nothing to earn and felt sure of some swift and terrible retribution. As I bit into that last strawberry, I began to weep because language, I felt, was no longer at our disposal, because there was nothing in the word that we could use. Nothing settled in place.

Amid explorations of self-effacement, obedience, inheritance, and examining the effects of relentless attacks on minority groups and the internalization that comes forth as a result, Study for Obedience is an unsettling tale that, while certainly not for every single reader, is both masterfully constructed as a form of art and hard to dismiss after turning that last page, lingering long after. You will have questions that will inevitably justify re-reads. This is the kind of novel that will warrant multiple revisits and would interminably be perfect for book club discussions. And is a personal standout read of the year.

Reply