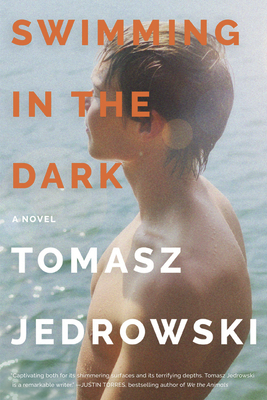

Love is political and desire is shame in this stunningly poetic debut.

Published by William Morrow

208 Pages. Full Length Novel

“We can never run with our lies indefinitely. Sooner or later, we are forced to confront their darkness. We can choose the when not the if. And the longer we wait, the more painful and uncertain it will be.”

Stories that centre the loss of innocence are universal for a reason. One need not look any further than the thousands of novels and films and televisions shows that have consistently relied upon this specific trope to support larger narrative ambitions. In Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s (1997-2003) fifth and sixth seasons, Buffy is forced to undergo rapid maturation given the (slight spoiler) abrupt emergence of a never-before-seen younger sister and (major spoiler) the very sudden loss of her mother. In Call Me By Your Name (2017) – a gay coming of age film, of which its source material is directly compared to the novel this review is directly concerned with – Elio sees a loss of innocence through a blazing and passionate affair with his father’s older and handsome graduate student. From the dark cemeteries of Sunnydale, California to the sun-soaked, languorous wineries and poolside loungers of Crema, Italy – both projects examine the loss of innocence through differing yet overlapping angles. The idea that a single individual can inhabit your life so thoroughly, only to vacate within a season’s timeframe. That the profound, resounding, impact is still very much palpable, despite their absence. These are themes that are evident in this stunning debut novel.

Jedrowski’s Swmming In The Dark (2020) is deceptively short, at only 200-pages. Yet, its emotional impact rivals the length of a novel easily twice, three times its size. Told in the first-person, Jedrowski frames the narration of this story retrospectively, through the lens of immigrant Ludwik Glowacki (who at the outset of the novel, resides in Brooklyn New York) reflecting on some time period in the past.

Tracing his early life and childhood in Poland through the country’s brief period of martial law, the outset of the novel begins with a recanting of his life prior to his immigration to the States. Ludwik has never particularly fit in, and this is especially prescient in Communist Poland during the 1980s, where being gay was a criminal offense.

The narrator recalls past lovers, Janusz (more on him later), and his first-crush. Ludwik first suspected he was gay when he felt an inconceivable, yet uncontrollable urge to kiss the older, 9-year-old neighbour boy Beniek. Just as Ludwik hoped to act on his physical urges, having come close during a co-ed Communion dance celebration, Beniek and his family inexplicably move away in the middle of the night.

Flashing forward to his early twenties, Ludwik is in transport on a bus out of Warszawa to a ‘work education’ youth training facility. It is there where he first lays eyes on Janusz, an individual that proves a pivotal figure in the trajectory of Ludwik’s life. Handsome, broad-shouldered, darkly charismatic and altogether forbidding, Ludwik feels an inexplicable pull to his peer, which is eventually recognized and thusly reciprocated.

“Some people, some events, make you lose your head. They’re like guillotines, cutting your life in two, the dead and the alive, the before and after.”

Both men develop a camaraderie, and eventual bond over menial activities such as moonlit, after-dark swimming in the nude, working out in the field in the sweltering sun, and an adoration of reading and sharing novels. One such novel, a central literary text foundational to the telling of this story, is James Baldwin’s ‘Giovanni’s Room’ – a novel that Ludwik feels wholeheartedly was written for him. In Communist Poland during the 1980s, such a publication was illegal due to its inclusion and depiction of homosexuality and its pertinent themes.

And while Janusz does become Ludwik’s great love, both men find themselves bisected by a chasm of opposing political beliefs. Once their stint in the work education camp, the haze of the ending summer and passion of close proximity concludes, they are cognizant that things cannot remain as they are upon their return to the city. Janusz has, indelibly, relegated an obedience to the existing power structure of the State and is resolved to mobilize upward. This ideological standing is something that Ludwik cannot comprehend, will never deign to concede to (or live freely within), and will never personally compromise on with Janusz, cultivating the distance between both men.

Ludwik believes personal freedom comes, inherently, from the ability to choose for yourself. This is unsurprising given his identification with Giovanni’s Room.

“It felt as if the words and thoughts of the narrator—despite their agony, despite their pain—healed some of my agony and my pain, simply by existing.”

Janusz believes his lot in life, his future, lies with the government, of the eventuality of working for the Communist Party, in order to improve his circumstances. In this, Ludwik knows that to live a life of authenticity, of integrity, would invariably represent the end of his romance and the beginning of a freely chosen life away from Poland.

Swimming In The Dark is phenomenal. It is seductive. It is heartbreaking. It possesses the same hazy, summer-hued warmth and sepia tones of Andre Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name. The moral dilemma posed by the choice between love, and pride, is one that is echoed in both this title and the aforementioned CMBYN, told in equally poetic and measured prose. This is a novel to be experienced, to be shared, to be cherished. My only real gripe is that I could have read more of Ludwik and Janusz’s story; at merely around 200-pages, Jedrowski truly leaves you wanting more, despite the flawless (though admittedly, again, incredibly heartbreaking) manner in which he wraps this story up. In this, Jedrowski captures the fiery passion of young love and the tumultuous nature of maturation to adulthood and its accompanying moral challenges and demands for compromise. This novel is a triumph, through and through.

Reply